By Jay Sjerven

December 28, 2021

100 years of international food aid:

Continuing the fight against hunger

The United States was engaged in what was at the time and for many years to come the world’s largest humanitarian mission ever, sending US food to Russia to save millions from starvation.

The need for US international food aid assistance is increasing, perhaps to historic proportions. The number of those living in extreme hunger has been mounting rapidly as the COVID-19 pandemic extends its grip on populations and economies. Even before the pandemic, millions of people suffered from hunger and malnutrition because of conflict, drought and natural disasters. Support in the United States for lending a helping hand to those abroad in need of food has been longstanding and broad based. In Washington, champions of international food aid have come from both sides of the aisle as the mission has been in accord with both the generosity of the American people and the national interest.

The United States government has depended greatly on private voluntary organizations to deliver in-kind food assistance abroad, and since 1961 has had a great partner in the United Nations World Food Programme, which has become the world’s largest humanitarian organization.

For this second of two installments on international food assistance, Milling & Baking News spoke with legendary champions of US international food aid and the executive director of the World Food Programme, and received a briefing from the US Agency for International Development on current US food aid policy.

Food aid champions come from ‘both sides of the aisle’

Historically, the US commitment to providing food assistance to the hungry of other nations has enjoyed support from Republican and Democratic leaders alike. Its champions have come from both sides of the aisle, and its future hinges on continued strong bipartisan support.

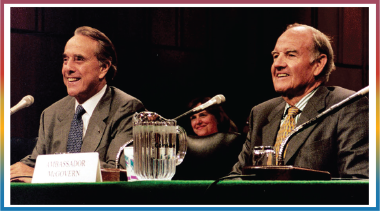

The late Senator Robert Dole of Kansas, former Senate Majority Leader and Republican candidate for President of the United States, was a towering champion for US international food assistance, especially in-kind food assistance, during his 35 years in the House of Representatives and the US Senate and for the rest of his life.

“I’ve always believed we have an obligation to help others in need — in this case, to help others who struggle to put food on the table,” Mr. Dole told Milling & Baking News in an October 2021 interview. “By feeding the hungry around the world, we make a real difference in the lives of others. Sharing our bounty has not only been good for US farmers, it’s also been excellent foreign policy. I believe there’s a link between a country’s food security and its stability as a nation.”

Asked why international food assistance enjoyed broad bipartisan support in Congress, Mr. Dole said, “I’d like to think that people from both parties equally recognize the humanitarian aspect of international food aid. When you think about it, it really isn’t a political issue, and it shouldn’t be a political issue. It’s a basic need of any human – to be fed.”

Mr. Dole left enduring contributions to the success and structure of US international food and agriculture assistance.

He and Senator George McGovern were responsible for the establishment of the renowned McGovern-Dole US International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program. Under this initiative, school attendance in select developing countries has been encouraged by ensuring children receive at least one nutritious meal at school each day. One standout achievement attributed to the program has been poor families increasingly sending their girl children as well as their boys to school. The program also has included innovative features such as rewarding students for school attendance by sending them home occasionally with a highly prized tin of cooking oil for use by their families.

“George and I created the program when we both met with President Clinton to discuss the issue,” Mr. Dole said. “It was clearly important to George and to me, and President Clinton also recognized the need. George and I both came from farming states, so we shared a mutual respect for farmers and a recognition that they should be instrumental in the ongoing fight against worldwide hunger. As for the future, I am confident that the momentum of the program will continue for years to come.”

Most of the food served in the school feeding program comprises US in-kind donations. Largely on the success and strength of this program, Mr. Dole and Mr. McGovern received the World Food Prize in 2008.

Mr. Dole emphasized the importance of donating US-grown food in its assistance to other nations.

“I’ve always believed that in-kind food donations are of paramount importance,” Mr. Dole said. “There is something special about sending our home-grown food to nations where there is need. It benefits the American farmer, and it benefits our relations with other nations.”

Asked what the future may hold for US international food assistance, Mr. Dole said, “We cannot feed the entire world – there is simply not enough food available here to feed all who are hungry worldwide — but we can help needy nations throughout the world increase yields and feed themselves. By sharing not only our food but also our science and expertise, we help foreign nations feed themselves and further close the gap between those who are fed and those who remain hungry.”

Sharing US farming expertise and technology was especially important to Mr. Dole, who in 1966 drafted legislation that called for a “Bread and Butter Corps,” which later became the Farmer-to-Farmer program, which continues to this day.

Sitting in on the White House meeting when Mr. Dole and Mr. McGovern made their pitch for an international school feeding program to President Clinton was then Secretary of Agriculture Dan Glickman, who oversaw the US Department of Agriculture’s food assistance operations including commodity purchases for donation abroad. Mr. Glickman said it was no mistake that Mr. Dole and Mr. McGovern jointly promoted the initiative as there has been a bipartisan foundation to all US international food aid programs.

Mr. Glickman told Milling & Baking News he was confident food assistance will remain an essential component in US foreign policy.

“Congress and administrations of both parties have supported food and nutrition assistance for many years, both bilaterally and through the UN World Food Programme,” Mr. Glickman said.

“The United States is the largest donor to the WFP, and I expect that support to continue,” Mr. Glickman said.

“The humanitarian challenges to food security, affected by climate change, weather variability and political conflicts, are likely to continue, and thus I would expect US food assistance will continue to be a high priority as part of our US foreign assistance programs,” Mr. Glickman asserted. “I should note that in these days of a highly toxic political environment in Washington, global food and nutrition assistance continues to enjoy strong bipartisan support.”

Mr. Glickman currently is a senior counselor and chair of the International Advisory Board at APCO Worldwide and is a longtime board member and now a lead director of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME Group). He is a distinguished fellow in Global Food and Agriculture at The Chicago Council on Global Affairs and an adjunct professor at Tufts University’s Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy in Boston. Mr. Glickman long has been engaged in promoting bipartisanship in the US Congress, retiring as vice president of the Aspen Institute and executive director of its Congressional Program in early 2021 after 10 years. Before serving as secretary of agriculture from March 1995 until January 2001, he represented the 4th Congressional District of Kansas in the US House of Representatives for 18 years.

“Traditionally our food aid programs provided direct commodity assistance to needy people,” Mr. Glickman said. “But while I expect that commodity assistance to continue, I believe that more assistance will be in the form of cash assistance, where the recipients can either purchase the food locally, or source it locally. Local conditions in those countries need this added flexibility, and this is a trend I expect to continue, so there will be a combination of cash and commodity assistance in the future. The key is flexibility, as there is no one size fits all in how food assistance is distributed. The US government has worked closely with the NGO (non-governmental organization) community, the WFP, and where possible, foreign governments in distribution efforts, particularly in high conflict regions.”

Mr. Glickman added, “I also expect there will be much more attention to issues of nutrition security, diet, health and disease, which have not been the top priority of our commodity assistance programs in the past. I can’t overstate the importance of nutrition and health, in addition to supplying US-grown commodities. This is a major domestic and global trend, and we need to be doing much more research into the types of commodities and food products that help promote good health and prevent disease.”

You might also enjoy:

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

Looking ahead, producers, processors and retailers must appeal to evolving demographics.

Today’s meat and poultry processors carefully manage expectations to feed people, preserve the planet and deliver profits in the future.

US-WFP partnership critical as world hunger is on the rise again

The need for international food assistance has grown dramatically in recent years and particularly since the disruption to global economies wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, David Beasley, executive director of the United Nations World Food Programme, told Milling & Baking News. Mr. Beasley is an American political leader, educator,and former governor of the State of South Carolina. He was appointed executive director of the WFP in 2017.

The WFP since its establishment in 1961 has been the most important partner to the United States in providing international food assistance, both in-kind and market based. In fiscal year 2020, 73% of US in-kind food assistance shipped abroad was distributed by the WFP, according to the US Agency for International Development.

“WFP fed 115 million people last year, more than in any other year in our history, and there are 42 million people in 43 countries at the ‘emergency’ phase of food insecurity in 2021 — just one step away from famine,” Mr. Beasley said.

“In this COVID period alone, we have seen the population of acutely hungry people double in the countries where we work, from about 135 million to 270 million,” Mr. Beasley said. “The chief causes are: man-made conflict (of the sort we see in places like Yemen and Syria); more frequent extreme weather like droughts and flooding; and the severe economic fallout from COVID, which has left so many people without money to purchase food. WFP has strong programs in each of these areas, one reason we received the 2020 Nobel Peace Prize for our work. For instance, WFP is helping 19 countries to forecast extreme climate events and trigger preventive action before vulnerable families are hit by disasters. By providing cash transfers ahead of floods, droughts and storms, we support people in harm’s way to evacuate assets and livestock, reinforce homesteads, and buy food, seed and emergency items so they are better prepared to deal with a food crisis.”

Commenting on the WFP-US partnership, Mr. Beasley explained, “The United States is currently the largest donor to WFP — and has been for our entire 60-year history. Last year, the United States alone contributed $3.7 billion of WFP’s $8.5 billion budget. That’s a strong vote of confidence by the United States, one that crosses political lines — and one that I don’t take for granted. We operate in close partnership with US aid authorities everywhere we work. Through various agencies like USAID and the USDA, the United States supports virtually every aspect of WFP’s work — our emergency operations, our livelihoods programs, our school meals work (WFP fed 15 million schoolchildren last year) and our management of the UN Humanitarian Air Service, which enables aid workers to reach remote areas not served by commercial airlines.”

Mr. Beasley was asked how methods of delivery of food aid have changed in recent years, and how WFP determines which method to use in different circumstances.

“WFP empowers its country teams to determine which specific mechanisms will be most effective in the local context,” Mr. Beasley said. “Different tools are better suited to different circumstances, based on factors ranging from availability of food in local markets to reliability of mobile phone services. As digital technology has opened up whole new ways of working, WFP’s methods of delivery have become more sophisticated, enabling us to reach hungry people more quickly and more efficiently. Even five years ago, who would have guessed WFP would be using drones to capture images of storm-ravaged areas unreachable by vehicles, so we can establish where the greatest needs are immediately after a disaster? Or send electronic vouchers by cell phone so families can buy food? We constantly embrace cutting-edge technologies in our drive to feed hungry people.”

Mr. Beasely replied “Absolutely!,” when asked whether US in-kind food donations will remain an important tool in the WFP toolbox in coming years.

“Although WFP increasingly provides direct assistance with cash (we have become the largest cash provider in the humanitarian community, supplying $2.1 billion of cash aid in 67 countries in 2020), in-kind donations from the United States and other countries will always remain an important part of the resources at our disposal,” he said. “We use different forms of assistance in different settings, based on local conditions, and in some places, using in-kind donations makes greater sense.”

Mr. Beasley said providing international food aid likely will become even more challenging in coming years.

“On the one hand, global needs are increasing due to the huge damage done by COVID, placing even greater pressure on WFP and on our partners to use precious resources as wisely as possible,” Mr. Beasley said. “On the other hand, the budgets of donor countries face their own pressures due to growing national needs from the pandemic and its economic fallout, so some countries are reducing aid. That is forcing WFP to reduce rations — something we never want to do. But I would urge our donors not to go down this path. If we act now, we can avoid the global hunger crisis spinning out of control, but if we wait for it to hit full force before we act, the costs will be immense. It’s all hands on deck. We need to act today.”

USAID: Robust food assistance across the globe

US international food assistance programs in the future will include continued donations of US-grown food alongside more recently employed methods of providing assistance to those in urgent need, including purchasing food commodities grown or raised in regions closer to a hunger outbreak, and even distributing cash or vouchers to refugees or other displaced families so they may purchase food readily available in local markets but unaffordable to them, a spokesperson for the US Agency for International Development told Milling & Baking News.

“The United States is the world’s leading donor of humanitarian assistance, providing more than $10.5 billion in fiscal year 2020,” the spokesperson said. “More than two-thirds of this funding— more than $7 billion—came from the US Agency for International Development, including nearly $4.8 billion in market-based and in-kind food assistance. The United States is committed to continuing to provide robust food assistance around the world.”

The spokesperson pointed out that in 2020, USAID’s Office of Food for Peace (USAID/FFP) merged with the agency’s Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance. The resulting body, the USAID Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance, “aims to elevate US humanitarian assistance to better respond to the magnitude, complexity, and protracted nature of today’s emergencies.”

The spokesperson said Congress appropriates funding for both the PL 480 Title II account, which provides for in-kind donations of US-grown food, and the International Disaster Assistance (IDA) account, which primarily provides for market-based food assistance.

“These two streams of funding allow USAID to draw both from in-kind US- grown commodities as well as the full suite of market-based food assistance modalities depending on the specific context on the ground,” the spokesperson said.

Asked what US international food assistance may look like in the future, the spokesperson said, “USAID is focused on providing the right assistance at the right time. Just as US food assistance has continued to evolve over our (USAID) 60-plus year history, it will continue to adapt based on the crises at hand. In-kind food assistance is, and will continue to be, a critical tool where markets are not functioning and food is scarce. We will also continue to draw from a full suite of market-based modalities, including local, regional, and international procurement, food vouchers, and cash transfers for food, where the situation on the ground makes those tools more efficient and effective ways to reach people in need.”

The spokesperson said USAID considers a variety of factors when determining the most effective means of providing food assistance, including the specific needs on the ground, what access it has to affected populations, market conditions in the affected area, and costs of transporting food assistance.

“In most cases, flexibility and complementarity are the keys to effectiveness,” the spokesperson said. “A combination of humanitarian response options is often the most effective way to meet people’s emergency needs. For example, Yemen receives significant in-kind food assistance because the country imports roughly 90% of its food supply, but an effective humanitarian response in Yemen requires not only in-kind food assistance but also market-based assistance through food vouchers.”

The product mix in US international food assistance has changed over the past several years with a greater emphasis on nutrition and not simply on providing essential calories.

“USAID provides food that best meets nutritional needs and local dietary preferences,” the spokesperson said. “These commodities may vary year to year based on where we are programming. Over the past decade, USAID has also been working to improve the nutritional value of our food products by using nutrient-fortified foods, such as Super Cereal Plus and Corn Soy Blend Plus, as well as ready-to-use foods (such as nutrient-fortified peanut butter pastes) that help address hunger while preventing and treating malnutrition.

“For example, in South Sudan, USAID is providing Ready-to-Use-Therapeutic Food (RUTF) through the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) to treat the most severely malnourished children, as well as fortified blended flours and vegetable oil and Ready-to-Use-Supplementary Food (RUSF) through additional partners to prevent malnourished children from deteriorating to a more severe state.”

There are currently 25 food commodities and products procured for use through Title II programs.

In order to ensure US-grown and processed foods reach aid recipients as expeditiously as possible, US farm and food industries for the past several years have encouraged pre-positioning of US products in warehouses closer to areas likely to experience food scarcity.

“Pre-positioning food makes USAID more agile and flexible to respond to crises as they emerge,” the USAID spokesperson said. “USAID stockpiles food in key locations around the world to significantly reduce the amount of time it takes to reach people in need. By getting a head-start on the lengthy procurement and delivery process, pre-positioned food arrives on average 76 days earlier than food procured normally. At any given moment, USAID has up to 50,000 tonnes of in-kind food aid stored in four warehouses around the world, ready to respond to crises as they arise. The composition and levels of the inventories are tailored based on anticipated needs and forecast demand.

“In fiscal year 2020, more than 170,000 tonnes of in-kind commodities were distributed to people in need from USAID’s prepositioned stocks,” the spokesperson continued. “Commonly pre-positioned food items include yellow split peas, vegetable oil, Corm-Soy Blend Plus, lentils, and cereals.

“USAID also works with the World Food Programme to maintain its network of warehouses throughout the world,” the spokesman added. “By extending the network, USAID and WFP can reach even more people in need of emergency food assistance.”