By Dan Malovany

April 2021

Passing the

Test of Time

For a legendary family business, embracing change while respecting its heritage remains the secret to longevity and ongoing success.

Sometimes it takes an unwavering hand for family bakeries to persevere through the best and worst of times.

In 1920 during the Spanish flu, German immigrant Herman Seekamp purchased a little Chicago bakery called Clyde’s Delicious Donuts. Fast forward to last year, when the Addison, Ill.-based company and one of the nation’s leading donut producers celebrated its centennial, this time again in the middle of another pandemic.

Now Kim Bickford, chief executive officer and third generation owner, took his turn to guide the bakery through another tough patch in the company’s storied history. He thought of his grandfather, who led the bakery through the Great Depression by maintaining an optimistic attitude and a cautious approach to the business. That’s a proven formula that’s worked so well over the years.

“When the pandemic hit last year, one of the important things that I said to the organization was, ‘This company has been through a lot in the past 100 years, and we’re going to get through this as well.’ That’s a steady message that I tried to share with our team,” noted Mr. Bickford, who’s been with the company for 44 years.

“I’m not patting myself on the back, but that’s the thing you have to do when you’re in a position of a family business where you care about the people who helped make you successful, and you have to reassure them that you’re going to be successful going forward,” he added.

“We’re conservative in our business, and we take care of our customers and our employees. Those are the things that help a family-owned business survive.”

Maintaining a sense of history and addressing new challenges allow family-owned bakeries like Clyde’s Delicious Donuts to focus on tomorrow, noted Josh Bickford, executive vice president, strategic initiatives and fourth generation family member.

“Even though we’re a family business, what’s best for the business comes first,” he explained.

“Having a lot of mutual respect in the family has made that conversation easier at any given point. We have never been afraid to pivot or change with industry trends.”

Breaking the rules

Too many legacy businesses, however, get stuck in the past.

“You’ve heard of the 100-year rule that says, ‘We have always done it that way.’ We try to get away from that type of thinking,” Josh Bickford said. “We have to have new ideas.”

This mindset is one of the many reasons why some family bakeries succeed and others do not, especially when faced with one of those many watershed moments in a company’s history. For Clyde’s, the latest turning point came just a few years ago, when the donut producer pivoted from fresh to frozen distribution to serve the shifts in the in-store bakery channel.

“That’s allowed us to grow dramatically because we reached new markets,” Kim Bickford said.

Pivoting is not a catchy phrase that suddenly became popular for Neri’s Bakery Products. Anthony M. Neri, general manager for the Port Chester, NY-based bakery, said it has been a key for survival for this family business that was founded in 1910. He’s a member of the fourth generation involved in the family business with Brett Neri-Ferraro, head of human resources; Anthony Frank Neri, plant manager, and Salvatore Neri Jr., manager of the sweet goods department.

“You always have to keep evolving and keep up with the industry,” Anthony Neri observed. “With everything that’s going on, we shifted to a lot of individually wrapped items, which weren’t as big in demand five years ago as they are today.”

One of the company’s pivotal moments came in the early 2000s, when his father Dominick, now president, and uncle Paul Neri, vice president, shifted the business to contract manufacturing for major food companies from fresh independent deliveries to delis, diners and pizza joints at night.

“We never stopped providing those normal route jobbers at night,” Anthony Neri recalled. “We diversified. We no longer had all of our eggs in one basket.”

That decision paid off in a huge way during last year’s pandemic-driven shifts in the market.

“There are a lot of smaller family-owned players that might not be around now,” he said. “If you are solely surviving on those pizza places and diners, you may be in trouble today.”

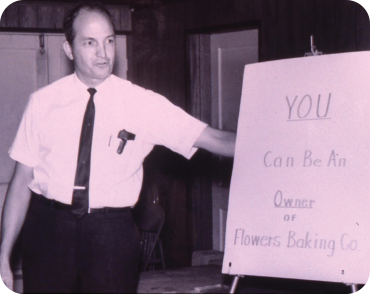

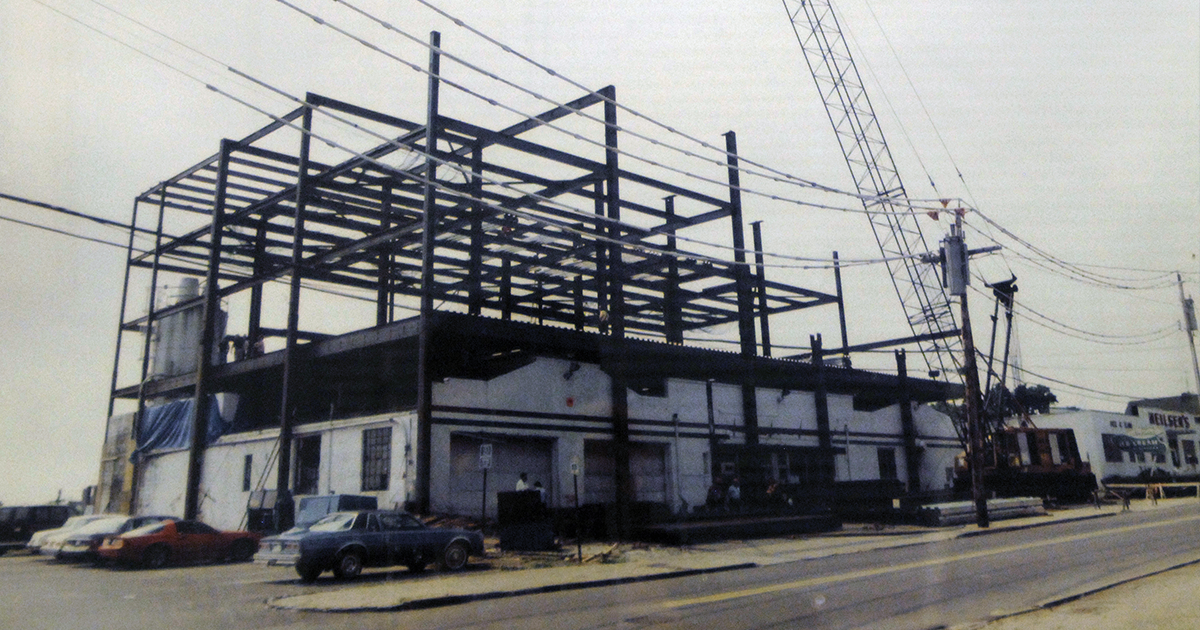

For Flowers Foods, which celebrated its centennial in 2019, the transformational moment came in 1968 when the family’s second-generation owners took then-called Flowers Baking Co. public.

“It gave Flowers a way to finance growth and acquisitions as well as make capital investments needed to stay competitive,” said Brad Alexander, chief operating officer of the Thomasville, Ga.-based company. “Looking back, going public was the one action Bill and Langdon Flowers took that all but ensured the company would survive the coming consolidation in the baking industry.”

As a publicly held company, Mr. Alexander added, Flowers became answerable to its shareholders, resulting in a renewed emphasis on accountability and professionalism. It began to actively mentor and promote younger employees into management positions and hire people with a business education and experience.

“Talking to people who worked for Flowers at that time, you will hear that the ‘Flowers family’ culture created by Bill and Langdon did not change when the company went public,” Mr. Alexander said.

“Fortunately, they were able to keep that strong sense of teamwork, commitment to hard work and the values of integrity and respect. Employees were offered the opportunity to purchase stock and many of them did.”

During the flurry of industry consolidations through the next few decades, Flowers made more than 60 acquisitions. Several factors came into play during this period.

“One is that many family-owned bakeries did not have the capital to modernize their operations, improve efficiencies or grow their businesses,” Mr. Alexander explained. “Another is that some owners had no viable succession plan, no one to take over the running of their companies.”

Additionally, he noted, consumer food preferences began changing more rapidly, and family-owned bakeries often didn’t have the money to invest in developing and launching new products. The retail food business also started consolidating at this time. As grocery chains expanded, bakers were forced to serve larger geographic areas, which was difficult for some with limited direct-store-delivery systems.

“For many family-owned bakeries looking to sell their businesses, Flowers Industries was the company of choice,” Mr. Alexander said. “While Flowers’ growth, culture and experienced management were attractive, the real draw was the company’s stock, which was performing very well. Many of the acquisitions at this time were either all or partial stock transactions.”

For some companies, long-term survival relies more on managing the family than operating the business.

“There is an expression that I heard a long time ago that the first generation starts the business, the second generation grows the business, and third generation either sells the business or blows it,” Kim Bickford said. “I’ve been here long enough. I guess we haven’t blown it.”

History is littered with dozens of reasons why family businesses fail, including family squabbles, sibling shareholders who want to cash out or heirs apparent searching for more exciting careers. Industry veteran Bill Zimmerman Sr. comes from a family of bakers where his father, part of the third generation, didn’t want to run the Colorado Springs, Colo., business.

Today, he noted, some companies face unfunded pension liabilities, which make it difficult, if not impossible, to sell. Inheritance taxes have ended bakery dynasties. Regional family bakeries have gotten squeezed by the demands that national, big box retailers put on their suppliers. And then once-in-a-lifetime events like the pandemic have forced bakeries to sell or to fold.

Perhaps the main issue involves the lack of skilled labor coupled with an aging workforce.

“From an operations perspective, we continue to kick the can down the street about educating our workforce to understand what manufacturing is about,” Mr. Zimmerman said. “We are in dire straits, in my opinion, about educating people and replenishing the vast amount of knowledge that we’re losing because people leave the industry. It’s not so much about the family but finding people who can support the company as it goes forward.”

You might also enjoy:

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

Looking ahead, producers, processors and retailers must appeal to evolving demographics.

Today’s meat and poultry processors carefully manage expectations to feed people, preserve the planet and deliver profits in the future.

Making the transition

At Neri’s Bakery, third generation Dominick and Paul Neri made a commitment to hand over the family business in better condition than when they received it.

“I can’t tell you how many times my father has been asked, ‘Why do we work so hard?’ and his answer every time is, ‘I do it for my kids and my grandchildren and nephews,’ ” Ms. Neri-Ferraro noted. “That’s a big part of why we’re standing strong as opposed to other businesses in our industry.”

Ms. Neri-Ferraro recalled how she would wake up some mornings and her father and uncles still hadn’t returned home from the bakery.

“They were always at work,” she said. “They’ve groomed us and shown us what it’s like to experience failure, and that’s a big part of why we’re so successful.”

Today, Neri’s fourth generation takes an active role in the bakery’s operation.

“We’re all here every day,” Anthony Neri said.

That doesn’t mean the older third generation doesn’t have a say in the business.

“The key to our success is letting them think that they still are in control and that they’re still holding the torch. No, I’m just joking around,” Anthony Neri said.

“They’re very much involved here. We try to walk in the footsteps of our father and uncles. They’ve clearly been doing something right for this business to be successful after all these years.”

At Clyde’s, Kim Bickford and his brother, Kent, who is retired, learned the ropes from their father, Bill Bickford, and from on-the-job training. Josh Bickford, however, was recruited back into the bakery for his IT and administration expertise after attaining a finance degree from the University of Illinois. Over the years, he’s received informal training in other parts of the operation as well as in marketing and sales. That’s something his father appreciates.

“The next generation always brings a questioning attitude,” Kim Bickford said. “Is there a better way of doing something? They come in with fresh eyes and fresh ideas. So that’s a key to success when the next generation joins the business.”

Among the changes included a new image and rebranding that leverages the fun of donuts with the “smiles all around” campaign.

“We have this wonderful legacy business of donuts, but there is not a more fun product to be making than donuts,” Josh Bickford said. “We have an opportunity to take that to the next level and be industry experts.”

Kim Bickford pointed to another key to long-term success: bringing in outside managers to support the family business.

“In my career we have hired some very good team members and leaders,” he said. “We have been very blessed to have had good businesspeople contributing to our success in the last three decades or more.”

At Flowers Foods, Mr. Alexander said, turning the century mark serves as a reminder that the 100-year rule is meant to be broken.

“One thing 100 years in business will teach you is that the only constant is change,” he said. “Everything is evolving and today faster than ever. If you don’t adapt, you won’t be around for another 100.”

During the past five years or so, he added, Flowers has taken a deep dive into all areas of its business and even established a transformation office to manage the success of its key initiatives that will shape the future of the company.

“Our digital projects are particularly exciting,” Mr. Alexander said. “When implemented, they will bring us even closer to the consumer, increase our operational efficiency and deliver real-time insights that will allow us to make faster and smarter business decisions. The three initial digital areas or domains we’re working on are e-commerce, autonomous planning and what we’re calling ‘bakery of the future.’ Our team is at the heart of this work. We’re committed to its ongoing development and building capabilities as one of our strategic priorities.”

At Clyde’s, Josh Bickford sees the potential future in his seven-year-old daughter and four-year-old son and the excitement in their eyes knowing that their father is the “cool dad” who makes donuts. And besides, who knows what the fifth generation will bring to the bakery?

“I think there are still plenty of donuts to be made,” he said.

That’s how a business keeps it a family affair.