By Joel Crews

December 2021

Humane

touch

Processors continue to elevate the importance of animal welfare.

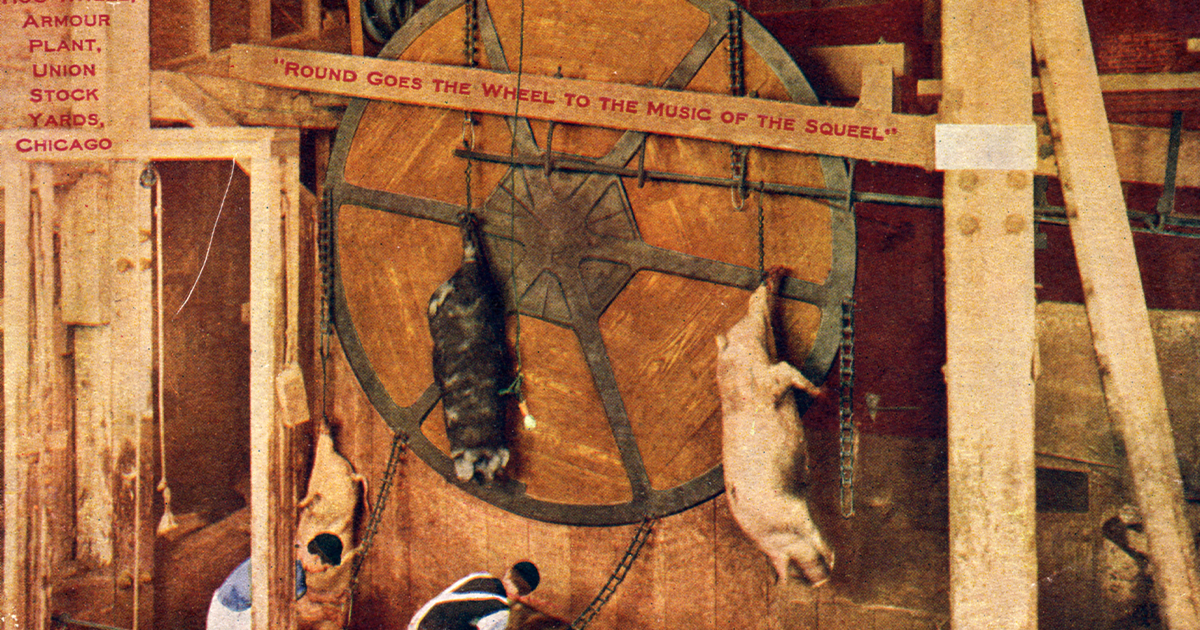

Heritage Image Partnership Ltd / Alamy Stock Photo

The relationship between man and beast has biblical roots and has long since garnered the attention of ancient philosophers and theologians.

“It matters not how man behaves to animals because God has subjected all things to man’s power,” Thomas Aquinas wrote.

The perception that animals, especially livestock, were merely a tool to facilitate the needs of people, including performing work and as serving as a source of food, was the subject of noteworthy philosophers.

According to the writings of Aristotle, “Plants exist for the sake of animals and brute beasts for the sake of man.”

Temple Grandin, PhD, a professor of animal science at Colorado State University and an expert on animal welfare and livestock handling designs, sees the relationship between humans and animals differently. The 74-year-old icon recently recalled a trip to Israel years ago when she conducted an informal survey of Hebrew-speaking residents about what they thought man having dominion over fish, birds, cattle and wild animals of the earth meant.

“Just about every one of them said it meant stewardship. That’s a very different meaning,” she said.

“That’s in the Bible,” Grandin said. “There was some concern about animals even back then.” Grandin, an educator, scientist, engineer, author of dozens of books and the subject of an Emmy-award winning movie, has dedicated her long career to improving the lives of animals.

Origins across the pond

The United Kingdom was ahead of the United States with regard to legislation related to humane treatment of livestock in the early 1930s as evidenced by the passage of the Slaughter of Animals Act of 1933, which required mechanical stunning of cows and electrical stunning of pigs.

Meanwhile, in the United States, the growth of the meat industry in the early to middle 20th century was facilitated by the establishment of stockyards in Chicago, Kansas City and New York and the use of feedlots across the country. The expansion of a transportation infrastructure brought exponential growth in livestock production as transportation advances made moving live animals from farms to feedlots to processing plants much more prevalent. The development of refrigerated transportation via railways and on trucks also served to distribute more meat to more states. As demand, production and consumption grew, so too did the awareness of how animals in the food supply chain were treated.

About 25 years after England’s formation of the Humane Slaughter Association (HSA) in 1911, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed the federal Humane Methods of Slaughter Act into law. Prior to the 1958 Humane Slaughter Act, there were no laws regulating humane slaughter practices. The initial law focused on ensuring that proper methods were used to render cattle insensible before shackling, hoisting, casting or cutting. The law applied only to companies selling meat to the US government and specifically addressed the stunning of cattle, pigs, sheep and other mammals, and did not address the stunning of birds. It also did not apply to religious slaughter, such as halal or Kosher.

The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act of 1978 was passed as a follow-up to the earlier law, addressing cattle handling practices during the slaughtering process. According to the USDA, the intention of the 1978 act was to prevent needless animal suffering, improve meat quality, decrease financial losses, and ensure safe working conditions. Compliance with the Act was ensured by USDA Food Safety and Inspection Service veterinarians overseeing slaughter at beef packing plants in addition to FSIS inspectors on the kill floor. The veterinarian enforced humane slaughter methods throughout the plant by observing methods of slaughter, ensuring corrective action was taken, and reporting inhumane treatment of cattle.

Poultry’s time

The Federal Poultry Inspection Service was established in 1926, which initially provided inspection of live birds at New York area train stations and poultry vending locations.

Vertical integration in the poultry industry, especially during the 1960s, served as an opportunity for producers to utilize new biological and pharmaceutical technologies that would advance broiler welfare for years to come. By the mid ‘70s, the poultry industry had evolved as researchers discovered the important role of nutrition, implemented disease eradication programs and took advantage of genetic-based improvements in the breeding process.

More recently, the National Chicken Council (NCC) developed the NCC Animal Welfare Guidelines and Audit Checklist in 1999, which has been adopted by chicken producers and processors to ensure the humane treatment of chickens. The guidelines are species specific, focusing on broilers and broiler breeders and address every phase of a chicken’s life to make science-based recommendations for the proper treatment of broiler chickens.

“The USDA has requirements regarding humane slaughter under the federal Poultry Products Inspection Act, and the slaughter process is monitored on a continuous basis by FSIS inspectors,” said Ashley Peterson, PhD, senior vice president of scientific and regulatory affairs with the NCC. “Companies may receive a non-compliance report relating to animal welfare and must take corrective action when they are not in compliance with FSIS directives.”

Peterson said the evolution in technology in chicken production has advanced broiler welfare, including housing ventilation systems, automated and sensor-based control of feed, water and temperature controls in production facilities as well as vaccines and nutrition regimens that advance the health of more broilers. She said consumers today want to know food animals are treated well by food companies they hold responsible for animal welfare.

Perception matters

The Humane Methods of Slaughter Act of 1978 signaled a significant tide shift in the industry and a heightened awareness among consumers about the treatment of animals. The perception of animals’ role in society among humans has slowly evolved and the concept of animal rights and animal welfare began to be reconsidered as research about animals’ ability to feel pain, sense fear and possibly possess souls became more widely held.

One of the world’s most-respected experts on animal welfare and animal behavior, Grandin said the first step in the slow process of improving animal handling in the industry was accepting that livestock have senses similar to humans. As a person with autism, Grandin said she and the animals she has dedicated her life to share the traits of being visual thinkers and hyper-sensitive to sensory-based stimulants.

“One of the first things that happened a long time ago was recognizing that animals can feel pain,” Grandin said, pointing out that for many decades, neuroscientists confirmed that animals experience fear.

Grandin was one of the first researchers published in the Journal of Animal Science addressing fear as a psychological stressor experienced by livestock during handling and transport. That groundbreaking research, titled, “Assessment of Stress During Handling and Transport,” was published in 1997.

“I got the ‘fear’ word and some of that neuroscience brain research into the animal science literature, in the veterinary literature, because for a long time you couldn’t say that,” Grandin said.

“It is completely recognized today that animals have fear; that animals have emotional systems.”

Despite the passage of the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act of 1978, animal welfare practices in the meat and poultry industry were sorely lacking. Grandin said even after ‘78, what was considered normal was nothing short of atrocious.

“The ‘80s were about the worst,” she said, and she realized there were opportunities for her to be a change agent. Another emerging force pushing consumers and food companies to change at that time were animal activist groups, including the People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS).

By the time the Humane Methods of Slaughter Act of 1978 was passed, Grandin had earned her master’s degree from Arizona State University, where she was a frequent visitor at plants there, including the Swift plant in Tolleson, Ariz., as well as a Cudahy pork plant near Phoenix. She recalled each company proudly posted signs in their lobbies promoting the use of humane slaughtering practices, realizing the importance of animal welfare well ahead of many companies. In the late 1980s, Grandin moved to Illinois to pursue a doctorate at the University of Illinois.

Her early work focused on improving chute systems. In the 1980s and early ‘90s, Grandin developed the industry’s first-ever center-track restrainer system, based on a concept from researchers at the University of Connecticut. Recognizing it as a more humane option to V-restrainers, Grandin adapted the university’s plywood prototype and modified it for use in slaughter plant environments. Establishing the correct use of the center-track restrainers in the early 1990s proved to be challenging, however, as some plant operators didn’t always use them correctly.

It was frustrating, Grandin said, to realize that some company’s operators assumed throwing money at a problem would automatically fix it.

“There were a lot of these systems out there, but a lot of people just tore them up and wrecked them. They were not managing. Too often people would just buy equipment and think it was automatic management,” she said, which was simply not true.

The same false mindset applied in adapting stunning technology in slaughter plants.

In one of the first slaughter plants she worked in, the Swift plant in Arizona, Grandin worked with engineers to eliminate two large stun boxes that held two cattle at a time, which often triggered stress in the animals. She replaced it with a V-restrainer and a ramp system (which Grandin referred to as the “stairway to heaven”). The center-track restrainer ultimately replaced the V-restrainer, but equipment alone isn’t a solution.

“You’ve got to maintain it,” she said, “and realize equipment evolves. The V-restrainer was a big improvement in high-speed plants over stun boxes. And the center-track restrainer was another improvement.”

Credibility counts

It was also during this period that Grandin was beginning to design curved chute systems to more effectively drive cattle and pigs. And her expertise in animal behavior and engineering was being recognized by prominent industry processors.

“In the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, I laid out handling systems for all the Cargill beef plants in North America,” she said. In the same period, Grandin worked with the American Meat Institute’s (AMI) Janet Riley (who was then the vice president of public affairs) to write the “Recommended Animal Handling Guidelines for Meat Packers,” which was published in 1991 and was the industry’s first voluntary animal welfare guidelines for meat packers. In 1997, Grandin went on to write “Good Management Practices for Animal Handling and Stunning,” which included an objective scoring system based on the guidelines to be used as a tool to measure and manage animal welfare practices at meat plants. The system measured stunning efficacy, insensibility, vocalization, prod use and falling down.

Jerry Karczewski, who was working as an operations manager at Taylor Packing in the 1990s recalled reading an article written by Grandin and published in MEAT+POULTRY about the new auditing system using an objective scoring system. He was intrigued by the guidelines and scoring approach and saw it as an opportunity to address a problem with cattle stunning that was discovered at his plant by a European customer. At the time he didn’t know who Grandin was and with a background in fabrication and focusing on improving the quality of production, he saw this new system as a way to solve a problem in the slaughtering area of the plant, which was not his specialty. But he was intrigued by the audit process and implemented it at his plant. After a few months, prodding, vocalization and slips and falls decreased.

“It improved our scores and it improved our productivity because calm animals and good stunning helped us be more efficient,” Karczewski said. Little did he know, he was responsible for making Taylor the first company to implement Grandin’s system, much to the joy of AMI officials and Grandin. A few months later, Karczewski was part of a panel discussion on animal welfare audits at the first-ever AMI Animal Care and Handling Conference in 1997. Minutes after sharing his experience with the audience, Grandin approached Karczewski wanting to hear more details about the success of the program at Taylor. Grandin and Riley then encouraged and supported him to assume the role of the first chairman of the association’s newly formed Animal Welfare Committee, a position that took his career in a new direction that he said was highlighted by working closely with Grandin for many years.

You might also enjoy:

Overcoming obstacles and chasing innovation, the pet food industry prepares for its promising future.

Today’s meat and poultry processors carefully manage expectations to feed people, preserve the planet and deliver profits in the future.

McChange

Due in part to pressure from animal activist groups, McDonald’s Corp. hired Grandin in 1999 to train its team of food safety auditors on animal welfare practices using the objective scoring system that was becoming adopted by a growing number of plants. Once training was completed, any plant supplying the burger chain was required to meet or exceed the auditing criteria. Once the auditing system was implemented throughout the McDonald’s system in North America, plants were able to identify and fix problems throughout the McDonald’s network of suppliers.

“When McDonald’s required suppliers to use the audit,” Karczewski said, “that was a world-changing event for the meat industry.”

“In six months, I saw more change than I’ve seen in my whole entire career,” Grandin said.

It didn’t take long for competitors, Wendy’s and Burger King to get on board, following the leader by auditing plants and investing resources in animal welfare.

The buy-in from McDonald’s in 1999 signaled a huge shift for any meat company supplying customers in the QSR segment and beyond.

Erika Voogd was one of the first McDonald’s humane handling officers. Voogd recalled how the plants she was working with when the new animal handling audits began were focused on efficiency and maximizing the number of head processed with little regard for the welfare of the animals.

“This meant that if every cow or pig needed to be electrically prodded to get them to enter a stun box or restrainer, it was common practice,” said Voogd, who has operated Voogd Consulting Inc. in West Chicago since 2003. “Nowadays, it is uncommon for the electric prod to need to be used more than 5% to 10% of the time and many plants have eliminated use almost completely.”

When Grandin’s system was introduced, electric prods could only be used to move pigs or cattle 25% of the time. Efforts to reduce balking, slipping and falling became a priority for suppliers of meat products to the world’s largest QSR chains.

“The plants needed to think smarter and eliminate the slippery floors and distractions that kept animals from moving forward,” Voogd said.

When it came to stunning cattle prior to the new animal welfare auditing system, it was not uncommon for multiple shots to be administered due to an agitated, stressed animal or a poorly maintained captive-bolt stunner.

“This was a typical process; double stunning cattle routinely,” Voogd said.

However, the new guidelines only allowed for a maximum of 5% of double shots when they were introduced in 1999 and then lowered to four out of 100 as of 2018.

“Plants needed to ensure that the stun tool was in excellent condition and strong enough to stun the animal, even as cattle and pigs became heavier and larger over the years. Also, the handling operators needed to develop calm handling methods to assure that the animals were not stressed when presented to the slaughter area for stunning,” Voogd said.

Today it is rare for Voogd to record a double shot during a one-hour audit at the plants she works with throughout North America. She said, at most, it is an occasional occurrence.

“The plants that maintain their equipment, handle their animals calmly and have strong enough stun tools just don’t experience too many issues,” she said.

Tools of the trade

Voogd added that technology has played a role in improving animal welfare. Implementing third-party remote video auditing of animal handling practices has been adopted by most of the major meat and poultry companies in the industry.

Stunning technology has also made great strides through the years, including captive-bolt stunners.

“They are stronger in caliber and force and more ergonomically acceptable for the operator. This has made stunning easier and less likely to fail,” Voogd said.

Chuck Bildstein agreed. The humane stunning and equipment specialist with Riverside, Mo.-based Bunzl Processor Division is an authority on the most effective tools to render livestock insensible. He said captive-bolt stunners today are not a one-size-fits-all proposition.

“There are now stunners designed for specific-sized animals,” he said. “Bulls, bison, sows and boars require a more powerful tool for better stunning results.”

Tools to ensure stunners are performing properly are another advancement.

“Stun testers provide plants the opportunity to confirm the stunner equipment is working properly before use. Electronic recordkeeping data collection to track long-term storage and trend information for each stunner is another valuable tool,” Bildstein said.

“The plants are also more aware of the importance of the stunners and how important maintenance and cleaning of the stunner is. The plants have specific SOP documentation on the stunner equipment that provides detail to the maintenance personnel as to the proper steps for maintenance,” he said.

Voogd pointed out that there has been a flurry of large capacity pork plants adopting CO2 stunning. This method allows for group handling and stunning of pigs versus electrically stunning one pig at a time in a single-file chute.

“This technology has dramatically reduced the stress on the individual pig and greatly improved the meat quality,” she said. “Electric prods no longer need to be used and relying on the pig’s natural desire to stay with pen mates helps to assure that they remain calm prior to stunning.”

However, many smaller-volume meat lockers still use electrical wands on pigs to stun them. Improvements in this equipment have also been positive.

“The change in 2010 to head-heart stunning versus head-only stunning greatly improved the likelihood of the pigs remaining insensible until they could be bled,” Voogd said.

Keeping solutions simple

For decades, Grandin has preached that most animal welfare problems can be fixed easily and don’t require tens of thousands of dollars in plant renovations, redesigns and makeovers. This was the case at the plants supplying McDonald’s and in most of today’s plants. For example, common issues like slipping and falling animals were fixed by installing non-slip flooring at plants and in loading and unloading areas. Most other issues were resolved by maintaining and repairing facilities as well as training and supervising workers.

At that time, there were 75 plants supplying McDonald’s, recalled Grandin, and only three of them required investments in expensive equipment.

“When it comes to handling and stunning, it’s much better now.” Grandin said.

During the process, it was discovered that one unfortunate reality is that some plants employed livestock handlers who enjoyed hurting and torturing animals.

“It’s not nice to say, but it was something we learned,” Grandin said.

One of the causes of animal welfare problems in the past decade was a flurry of mobility issues in cattle. Causes ranged from the use of feed additives (beta agonists) during warm weather to genetic complications causing leg conformation problems in cattle and hogs.

“A calm person makes a good animal handler,” Grandin said. “Good handling takes a lot of walking due to the need to bringing up small groups of animals at a time.

“Handling is not a flunky job; it’s a really important job.”