By Laurie Gorton

July 5, 2022

Leveraging news -

The Food Business News story

Business intelligence and market analysis address the needs of readers throughout the food processing industry.

Intelligence is among the most basic needs of a business — information about its industry, competitors, suppliers, customers, innovations and consumer trends — plus, of course, analysis of how each impacts an individual business. That’s the assignment Sosland Publishing gave to Food Business News.

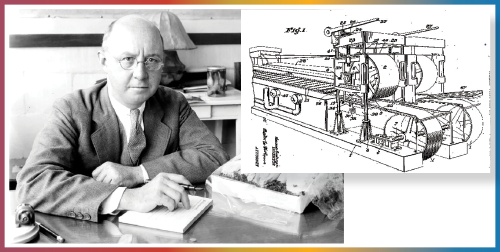

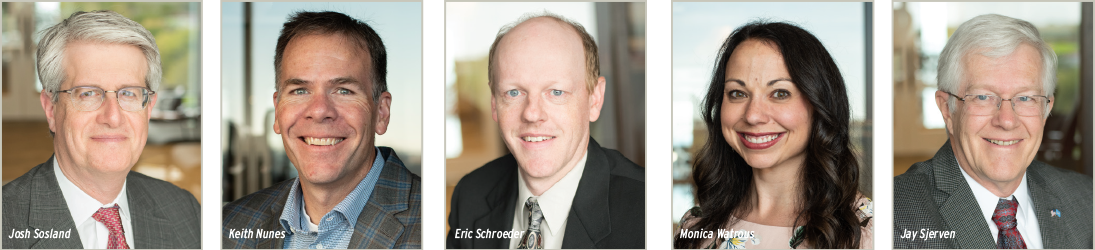

“The goal of Food Business News is to keep its readers fully abreast of developments within the food industry that will determine the well-being of their businesses,” wrote the magazine’s founding editorial team, Morton Sosland, editor-in-chief; Josh Sosland, editor; and Keith Nunes, executive editor, in comments opening its first issue, March 8, 2005.

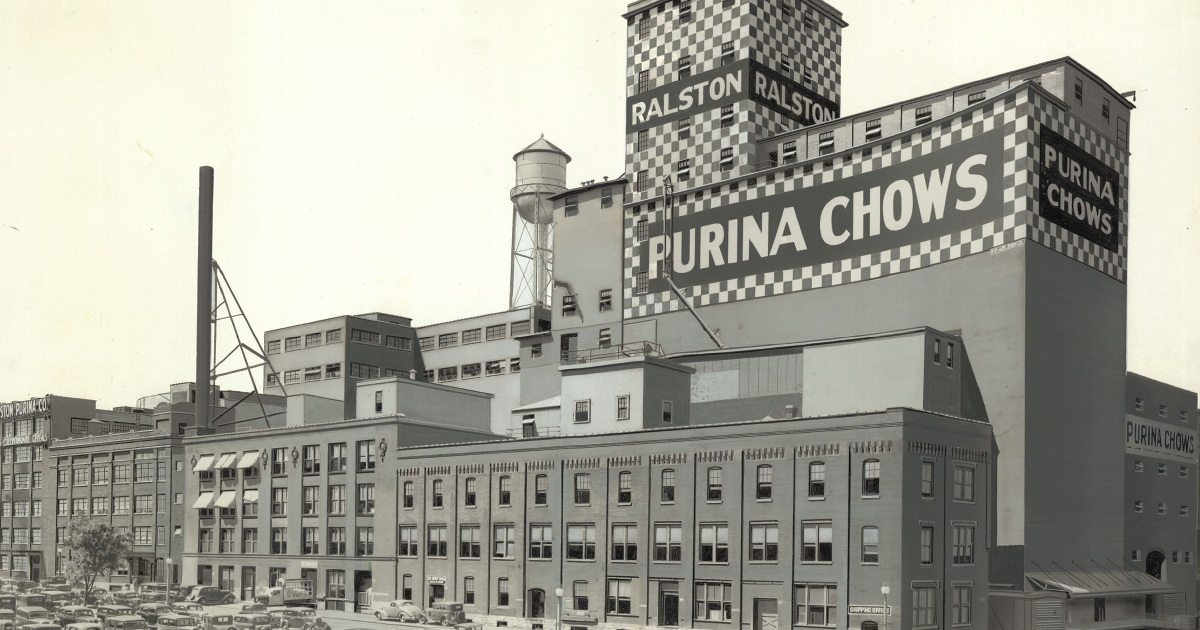

When Sosland Publishing created Food Business News, the company did something extraordinary in the business-to-business publishing world. It took its flagship grain-based news magazine, Milling & Baking News, and reduced its weekly publishing frequency by half. Then it created a new title with broad circulation across the entire food industry to slide into those alternate weeks. It extended the expertise of its editors, reporters and market specialists into broader coverage areas but kept the continuity of a weekly schedule.

“We decided to be about the business of food and beverage product development,” Mr. Nunes, now editor of Food Business News, said. “The competing magazines deal with processing methods and science, respectively, but we deal with the business — the strategies, the supply chain and the products.”

A risk that paid off

Within two years of its founding, Food Business News vied for the No. 2 spot among the six magazines that then comprised the market. Today, 17 years later, it is clearly the leader. Counting its print and digital editions, e-newsletters, page views and pass-along circulation, Sosland Publishing claims more than 2.2 million average monthly opportunities for advertisers to reach customers.

“After the first two years with Food Business News, we never looked back,” said Bruce Webster, associate publisher. “We became the leaders, certainly in competitive terms. The food trade press went from a six-horse race to maybe three titles.”

What prompted Sosland Publishing to launch Food Business News?

As its editors explained in their opening editorial, two powerful currents combined to create the new title: “One is the realization by the publishers of Milling & Baking News that its coverage of the grain-based foods industry has gradually stretched beyond the once narrow confines of wheat markets, flour milling and baking. (Its) readership has likewise expanded to include executives who were once not even considered likely subscribers.”

The company’s Purchasing Seminar, too, showed the same trends: more attendees from the food industry and more topics beyond bakery commodities.

From a revenue standpoint, suppliers to the $900 billion food processing market offered Sosland’s sales staff opportunities to court advertisers who had never been in the pages of the company’s magazines before.

Mark Sabo, then president of Sosland Publishing, had these facts in mind when he called a strategic planning session in the early 2000s.

“Mark drove this process, and Food Business News was the result,” Josh Sosland, editor of Milling & Baking News said.

Until then, Sosland Publishing had no product to attract the massive ingredient advertising segment, said Dave DePaul, associate publisher, Food Business News.

“Thus, we positioned Food Business News as an R&D, marketing and management reach that offered timely industry news, new product and new ingredient technologies to attract those ingredient advertisers,” he said. “At the time, all other ingredient-oriented magazines were monthly, and digital products were not as prevalent as they are today. There were new product books but none that presented timely content to the ingredient buying teams. Our audience gained momentum very quickly.”

Mr. DePaul, who joined Sosland Publishing at about the same time, had previously served as the associate publisher for a competitor magazine also in the food processing space.

“He gave us immediate credibility and controlled a huge portion of that business,” said Mike Gude, publisher of Food Business News, Milling & Baking News and Baking & Snack. “He helped jumpstart our foray into food ingredients.”

Managers also studied how potential readers might view such a publication, particularly its frequency.

Mr. Webster added, “When you look at how Food Business News and Milling & Baking News work internally, we are still publishing a weekly but covering two markets, one being grain, milling and baking, and the other being the food processing industry. And when we discussed the concept with important ingredient advertisers, they loved it and supported the magazine from day one.”

Mission oriented

Food Business News is described as the food and beverage industry’s source for the latest news, trends and innovations. The platform covers the entire food and beverage supply chain, from markets and product development to manufacturing, distribution and consumer trends. Food Business News’ content targets the needs of industry executives in corporate management, general management, R&D, purchasing and marketing.

“That mission has stayed the same over our 17 years,” Mr. Nunes said. “The magazine’s strength is its commitment to news and ingredients, especially as they affect new product development.”

The magazine’s focus on news and markets is now well understood by reader and advertiser alike, Mr. Gude said.

“We are unique in our coverage in that we publish twice a month and, most importantly, in that our editorial team understands the industry well and is adept in both print and digital mediums,” he said. “No other publishing title can offer those qualities.”

Mr. Nunes noted, “We are primarily a news service for the food industry — news of companies, news of ingredients, news of commodities, news of supply chain conditions.”

That information flows into Food Business News and its daily e-newsletters and weekly Strategic Insights e-newsletter; the Food Entrepreneur supplement along with its e-newsletter and Food Entrepreneur Experience interactive events; the New Food Insider new product e-newsletter; the Food Business News website; the Sosland Morning Briefing e-newsletter; and the Purchasing Seminar and Trends and Innovations Seminar.

Readers have always self-selected their preferred media channels, and this trend is reflected in how Food Business News readers interact with the magazine and its many channels.

“I measure reader engagement by web metrics,” Mr. Nunes said. “With the internet numbers, we can gauge engagement. It is much broader today than when we started up. It involves more people and more job titles throughout the food industry’s supply chain. And we’re getting significant participation from overseas, from Europe and Asia.”

Another way to describe the acceptance of the magazine’s print and digital acceptance from readers and advertisers alike is, as Mr. Webster put it, “The barrier to entry by competitors is just too high.”

Food industry trends

The Sosland Centennial marks not only 100 years in business for the company but also a century of change affecting its audience. The period witnessed huge advances in food safety and food regulation. For most Americans, fresh and processed foods are plentiful, yet food insecurity remains a problem for some populations.

Enrichment of grain-based foods, a key advancement of modern nutrition, had a controversial start in the waning days of World War II. With the addition of folic acid 20 years ago, enrichment continues to do its good work and has been so reported by the Sosland newsweeklies. Even so, attention continues to focus on food’s problematic role in obesity and related health and nutrition matters.

Food processing has always have been marked by emerging trends, with plant based being the most recent. And debate still rages over natural vs. processed and genetically modified vs. non-GMO. The revolution underway in retailing continues, especially during pandemic. And globalization, now more than ever, affects the food processing industry’s supply chain.

From a subject matter standpoint, “the pandemic has meant more eating at home and less at foodservice,” Mr. Nunes said. “Global warming is seen through reports on renewable agriculture and sustainable sourcing.”

Global commodity markets became unstable during the Great Recession of 2008–10, Mr. Nunes said.

“Now, during the past few years, commodity markets have again become less predictable with greater price swings,” he said.

“Everything happens so much more quickly today,” Mr. Webster observed. “For example, plant-based proteins are leaping off the charts right now, and a major miller is advertising carbon-neutral flour.”

The benefits of experience

From the start, Food Business News had the advantage of experienced editors and sales staff. Born of Milling & Baking News, the new biweekly could tap Morton Sosland and Josh Sosland for its top editorial positions. Mr. Nunes, then editor of Meat+Poultry, joined as executive editor.

The new publication’s approach emphasizing news, markets and news-oriented features worked well, Mr. Nunes said.

“Josh and the Milling & Baking News staff had expertise in market coverage, bakery and grain-based foods, and I was knowledgeable about dairy, meat and poultry matters,” Mr. Nunes said.

They recruited Donna Berry, a contributing editor with expertise in dairy and ingredients. From that base, the magazine was able to fill in the other industry segments — confectionery, frozen foods, produce and so forth.

For several years, Eric Schroeder, managing editor, Milling & Baking News, acted as the new magazine’s managing editor and later executive editor. Today, Monica Watrous is managing editor.

“I am not aware of any other magazines that use a shared staff quite like Food Business News and Milling & Baking News,” Mr. Schroeder said. “The adaptability of our staff really sets us apart, and I’m always impressed by our editors’ ability to seamlessly transition from milling and baking coverage to coverage of the broader food and beverage categories on a weekly basis.

“Many publications have ‘beats’ that writers are assigned to cover. That’s just not how we operate. Our editors are expected to have a broad skill set, and I think that shows up in the quality of the product.”

Food Business News was built on the Milling & Baking News model of providing its readers accurate, timely and vital information but with important differences, said Josh Sosland.

“The new publication’s approach to this mission grew almost from the outset,” he said. “The vast scope of its coverage created challenges and, at the same time, was liberating. Because attaining the intimate, granular involvement in all the segments of the food and beverage industries would be impossible to do along the lines of the Milling & Baking News model, Food Business News is able to devote greater resources to coverage of macro issues — the major trends driving the food and beverage businesses and the explosive growth of entrepreneurship in food and beverages.”

Essential market reporting

Nowhere in Food Business News does expertise matter more than in commodity market reporting. Among the most volatile costs a food processor faces are those of its ingredients. While weather factors into harvest and yield, geopolitics plays an even bigger role in availability and supply chain.

“Market reporting gives the magazine a core focus on ingredients that is directly related to product development,” Mr. Nunes said.

Josh Sosland, who started his career at the company as a market reporter, explained further.

“Market reporting helps ground the content in each week’s issue with in-depth updates about an important driver of industry profitability,” he said. “Because their profit margins historically have been wider than is the case for baking companies, large CPG (consumer packaged goods) businesses in the past were not as interested in keeping up with ingredient market trends. But over the last 10 to 15 years, they have sharpened their focus on costs because of flattening top-line growth. The attention paid to commodity prices has heightened considerably. The timing of Food Business News’ entry into the market was ideal.”

In the scope of its subject matter, Food Business News reports on the topics of trends and technology, as do its competitors.

“But we differ by covering company strategy,” Mr. Nunes said. “We report how corporate strategies affect product development and how they apply to the supply chain.”

Digital mastery

“We have built a loyal audience in the past 17 years and found that Food Business News content plays well on the internet as well as in print,” Mr. Gude said. “We deliver content in the form that our readers choose: print, digital, mobile, etc.”

At the time Food Business News was introduced, there was nothing like it in terms of timeliness and editorial position, said Mr. DePaul.

“Fast forward to today, and our content is still timely, but as all industrial food publishers have transitioned from print to digital, the timeliness position has become less of a differentiation,” he said. “All our titles are now in the webinar, e-newsletter, eblast, run of site and podcast business.”

The magazine observes no print/digital divide. Food Business News takes an omnichannel approach to its mission, employing print and digital as well as virtual and in-person events and nearly everything in-between. It was the first title launched by Sosland Publishing after the company established its presence on the internet. Because digital is still relatively new to the trade marketplace, Sosland Publishing counsels its advertising customers on how best to reach their audiences.

“It is our role to help our marketing partners be most effective in their marketing campaigns,” said Meyer Sosland, chief operating officer of Sosland Publishing.

Sosland Publishing’s digital expertise proved to be a boon to Food Business News.

“Even as we created new digital offerings, we maintained our print revenue,” Mr. DePaul said. “Early on, we benefited from the print-to-digital shift as we expanded our creation of complementary digital products. The combination of print and digital mediums reinforced the already timely and strong content of the title.”

More generally, he observed, “the percentage of print to digital has been changing drastically over the years, which lends itself to many challenges, short term and especially long term. I tell my customers that ‘content is king,’ and however our readers — their customers — want to read our timely and important content, they have many options with Food Business News and Sosland.”

You might also enjoy:

Business intelligence and market analysis address the needs of readers throughout the food processing industry.

Sosland Publishing’s new publication offers insight into a dynamic industry.

Monthly magazine explores how, where and why supermarket innovations happen.

The entrepreneurial difference

A growing number of startups entered the food and beverage marketplace in the past decade, triggering profound change across the industry. Created for executives interested in new concepts and the people who develop them, Food Entrepreneur offers insights into the disruption effected by up-and-coming brands while profiling the industry’s most successful and intriguing founders.

Food Entrepreneur debuted Jan. 7, 2020, as a supplement to Food Business News. Its content is the responsibility of Monica Watrous, managing editor, Food Business News. Its reports are posted on the website foodbusinessnews.net.

“For nearly 20 years, Food Business News has offered readers comprehensive and authoritative coverage of a rapidly changing food and beverage industry,” Ms. Watrous said. “The launch of Food Entrepreneur represents a sharper focus on the most exciting and consequential force in the sector today, offering the unparalleled reporting and analysis of developments critical for food industry executives to understand.”

Josh Sosland, president of Sosland Publishing Co., observed, “Food Entrepreneur was an organic expansion from Food Business News, based on what we saw as amazing reader response to Monica’s success in tapping into the entrepreneurial community. Her writing has attracted a following within the ecosystem of those starting up food businesses, but the reason we believe it will be financially successful is that the existing CPG industry is so keenly interested in quality content about food entrepreneurship.”

Food Entrepreneur’s content targets the many startups now entering the food and beverage marketplace. Food Entrepreneur highlights the innovation emerging from early-stage brands, while offering an inside look at the fundamentals of launching and scaling a food business.

“The people involved are not only the managers downsized by larger companies and looking for new opportunities but also a growing cohort in their 20s and 30s who are taking on roles that combined the C-suite with purchasing, processing and R&D,” said Keith Nunes, editor, Food Business News. “Through Food Entrepreneur, they can engage with their peers.”